Every attribute a plant has comes at a cost and every weakness has a corresponding strength. The strong selective pressure in the jungle out there ensures this.

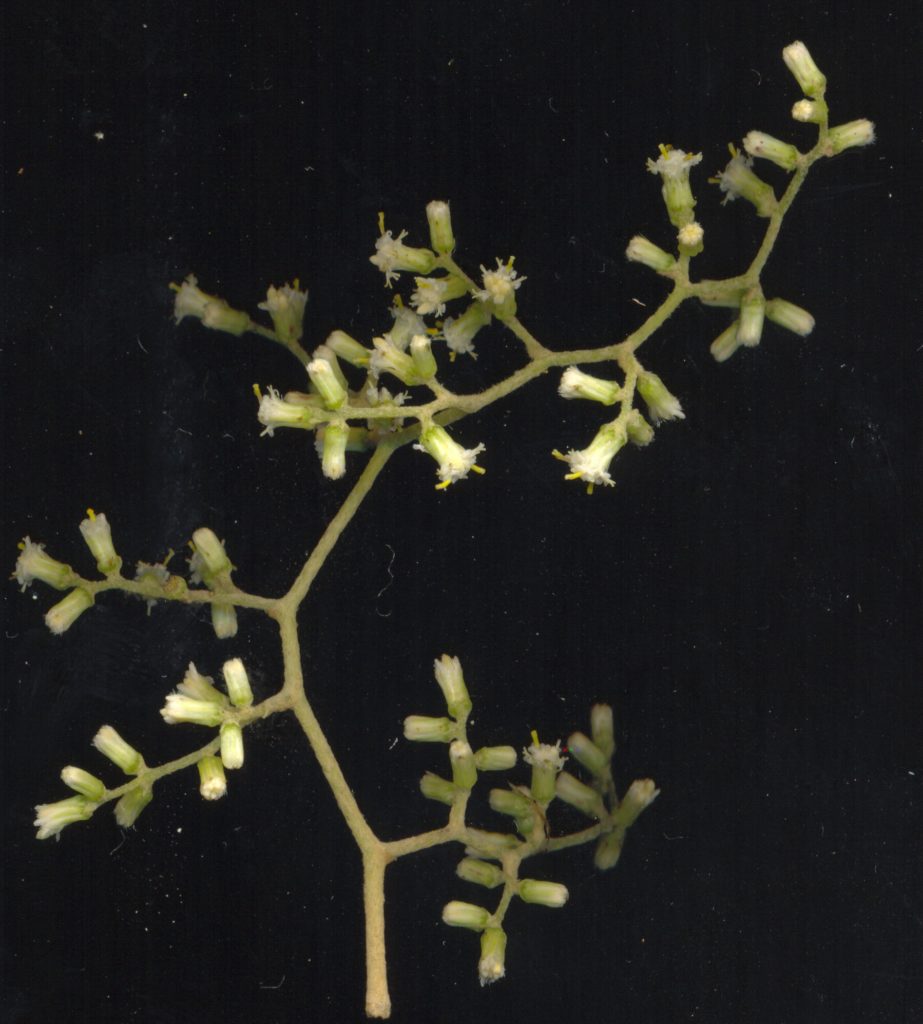

Brachyglottis repanda rangiora flower

Brachyglottis repanda rangiora flowerThere are plenty of understorey shrubs which will cope well both with intermittent flooding and with drought.

Rangiora is not one of these.

Rangiora does not have strong roots. Waterlogged soil, even for short periods spell disaster just as much as dry periods do.

I have sometimes grown fantastic specimens but I have had plenty of disasters as well, with whole lines of seedlings dying unexpectedly so I have learned to be careful.

Brachyglottis repanda rangiora flower

Brachyglottis repanda rangiora flowerDespite this Rangiora is a common shrub throughout most the the north island and mild parts of the south island so it must have some real attributes.

It does.

Rangiora will grow really well and quite quickly even in quite deep shade. So long as the roots are well drained (aerated) and consistently moist.

Brachyglottis repanda rangiora_seeds

Brachyglottis repanda rangiora_seedsThe masses of tiny seeds, each with their own parachute or sail made up of fine filaments like dandelion seeds do, catch the wind, the occasional lucky ones finding that ideal ground where they will thrive.

Last month we discussed Porokaiwhiri which takes about a year for the quite big fruits to develop.

Rangiora take about a month from the flowers opening until the fluffy seeds start to blow away in the wind during November.

So plant Rangiora in shady moist well drained places and it will grow spectacularly well.